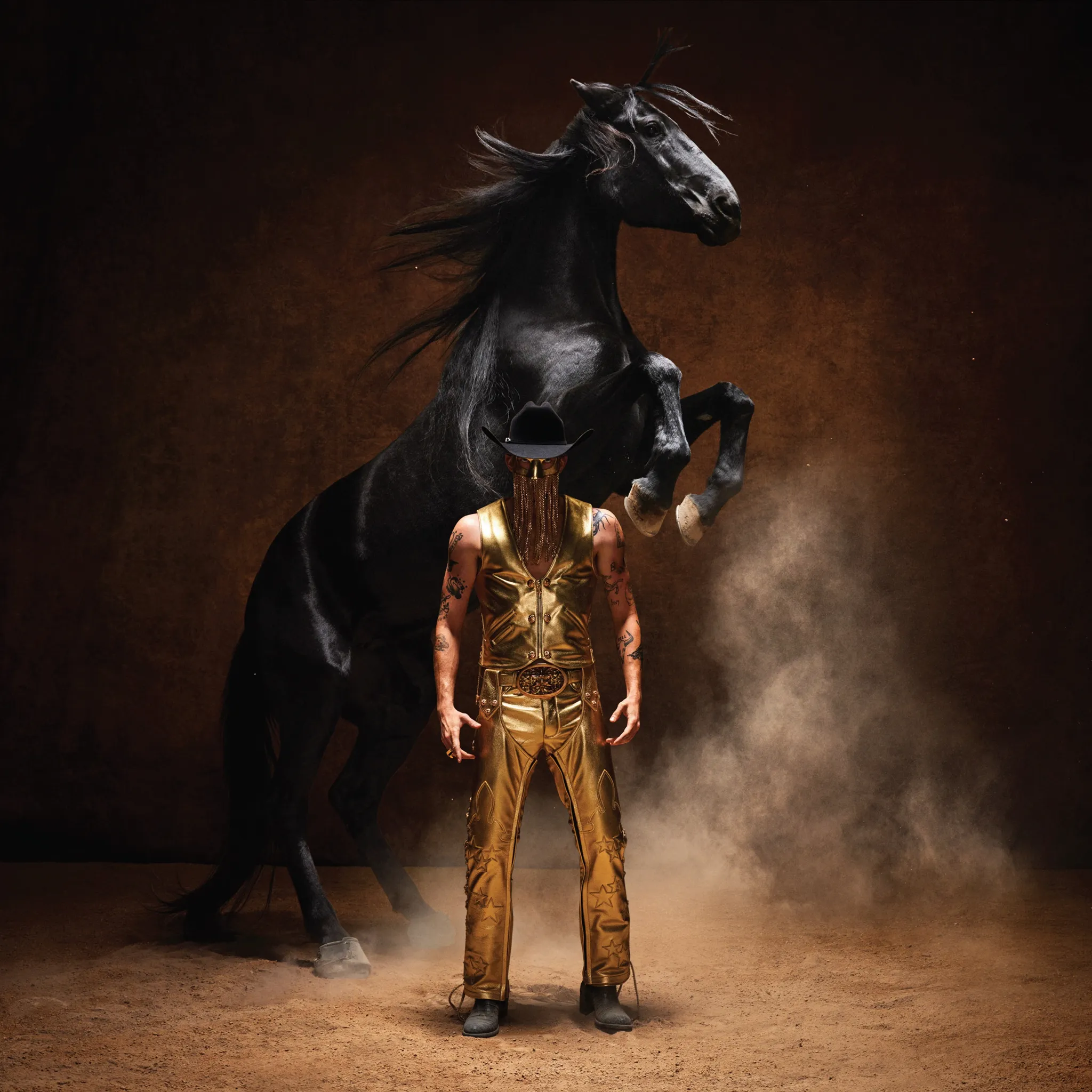

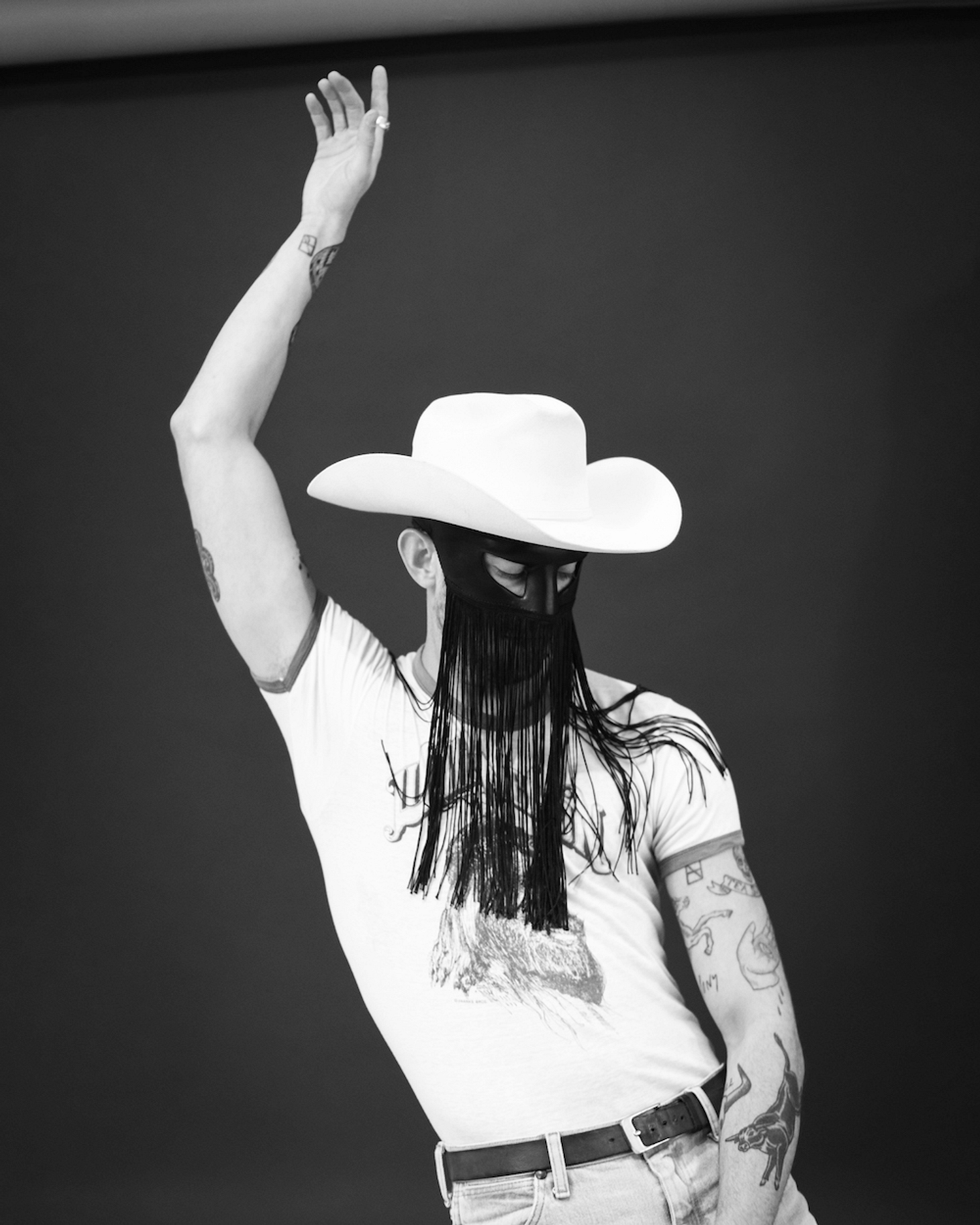

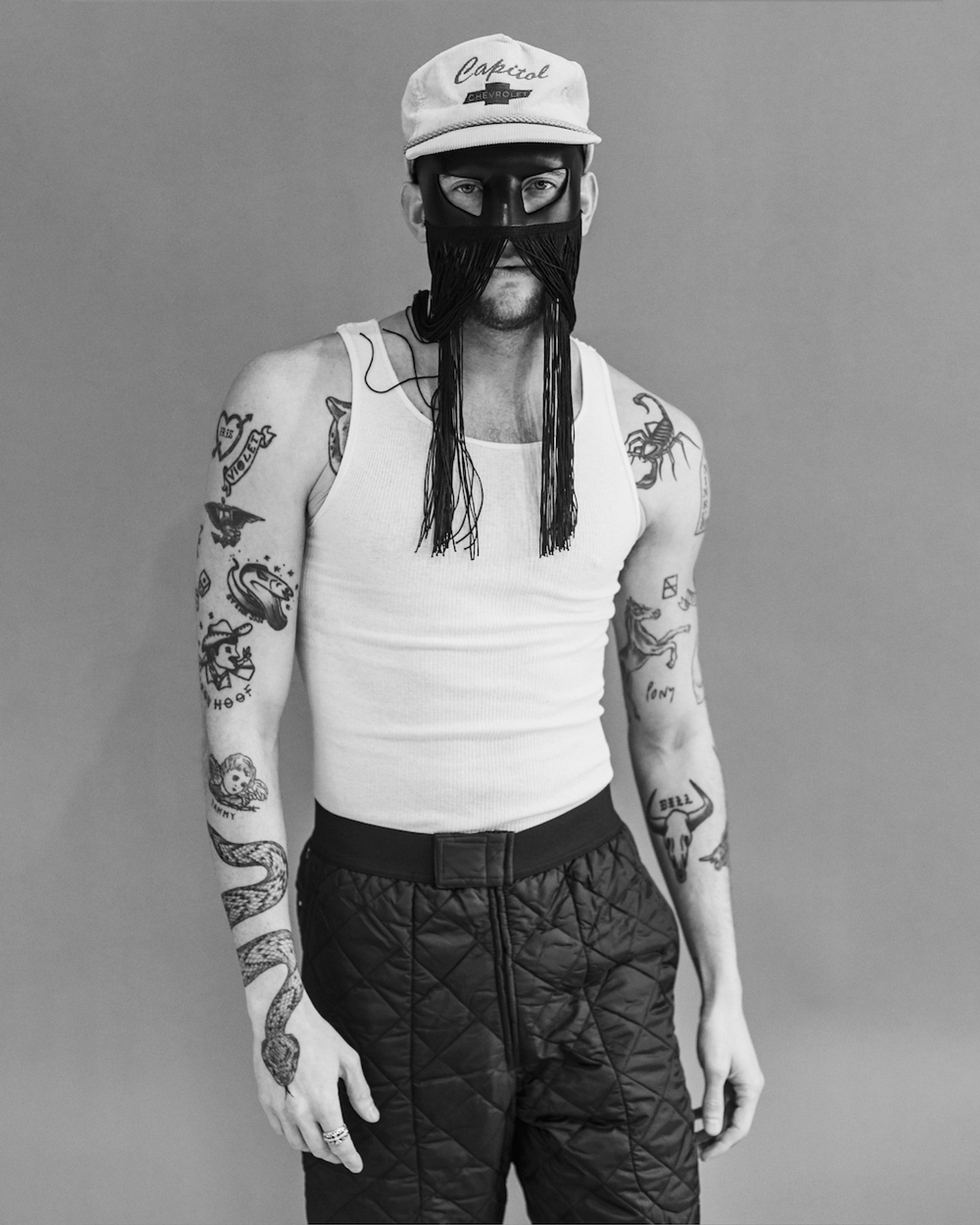

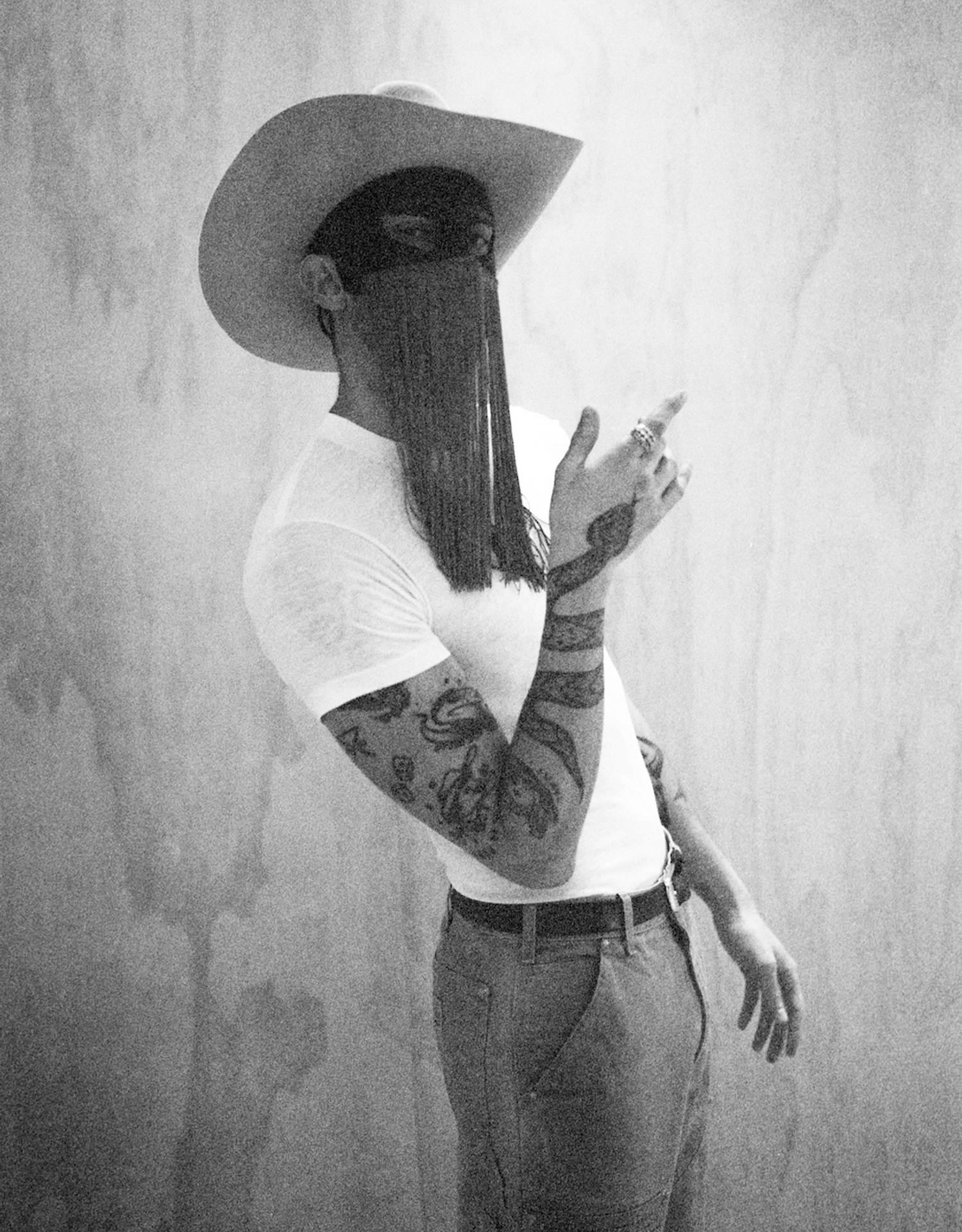

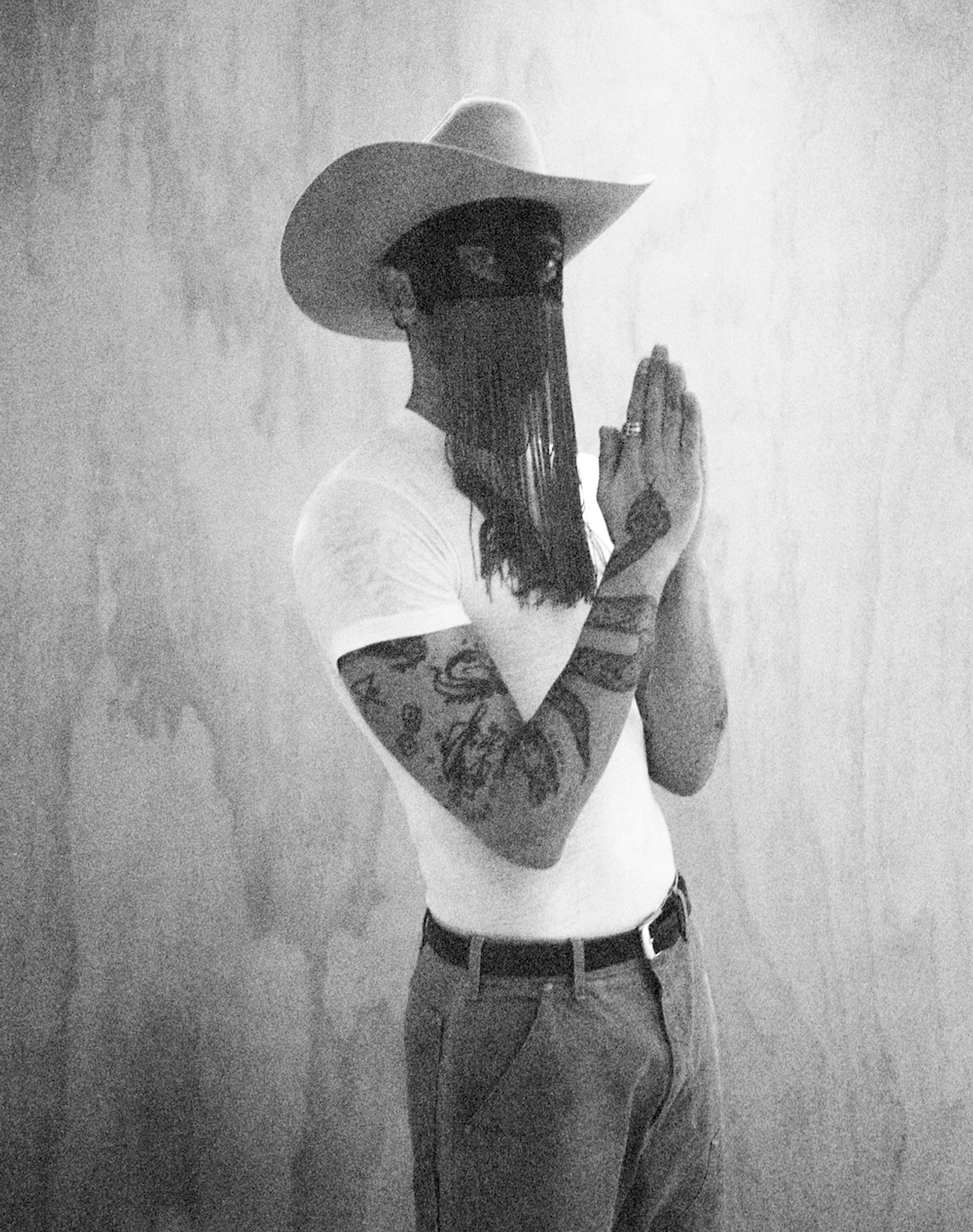

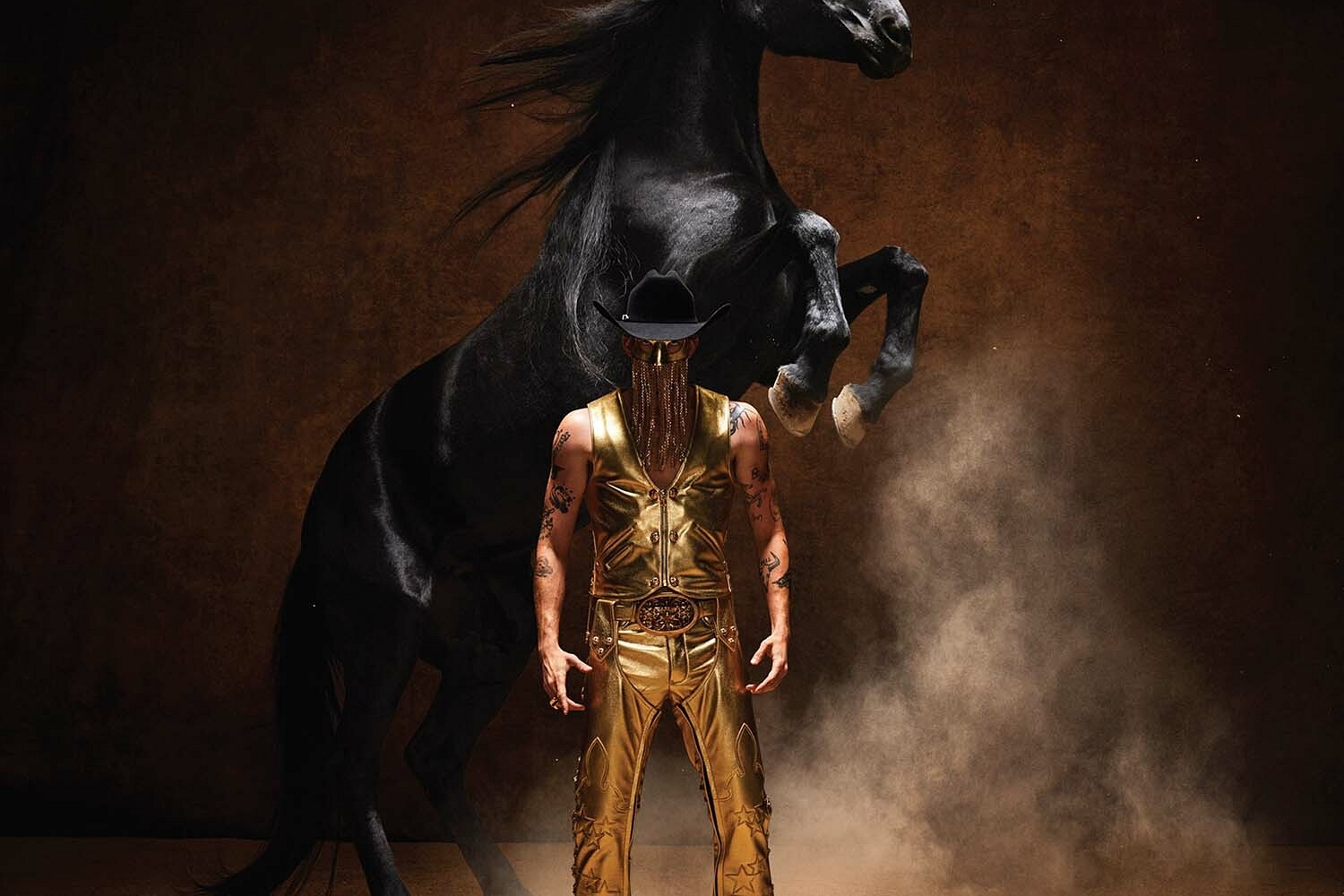

Interview The Greatest Showman: Orville Peck

Presenting country through a proudly campy, queer lens, Orville Peck has been changing the game since cantering into view with debut “Pony’. On “Bronco’, he’s taking us on an even more untamed ride.

You can’t talk to Orville Peck without asking about the mask. Whether he’s opening for Harry Styles at Madison Square Garden, modelling for Beyoncé’s Ivy Park Rodeo collection or duetting with Shania Twain in their ‘Legends Never Die’ video, his signature fringed mask always stays on. Since he emerged in December 2018 with ‘Big Sky’, a gorgeously haunting country ballad about a failed relationship (“I like him best when he’s not around”), Peck has never publicly shown his face. When he jumps on a Zoom call from Nashville, where he’s “doing a little work” ahead of the release of brilliant second album ‘Bronco’, it’s no technical glitch that the camera isn’t switched on.

As his profile has grown to the point where Lady Gaga is asking him to cover one of her songs – last year, he put on a Nashville spin on ‘Born This Way’ – he has been too clever to spoil the effect by supplying concrete biographical details. Orville Peck is a stage name like Lana Del Rey or David Bowie. We know he is Canadian and grew up “somewhere in the Southern Hemisphere”. Today, he tells DIY that he spent “almost five years” living in London in his late-twenties shortly before he introduced Orville to the world, which presumably puts him in his early-to-mid-thirties now.

Orville’s musical brilliance was confirmed by 2019 debut album ‘Pony’, a glowing showcase for his rich baritone voice, emotive storytelling and retro country style. He called it “a love letter to a classic country album”, but few of those have a song like ‘Queen of the Rodeo’ in them, which he wrote for Vancouver-based drag queen Thanks Gem. In a way, the fact Orville is so open about his queerness, both in interviews and his lyrics, only makes the other, unknown aspects of his identity more tantalising.

“I really love being this source of [queer] visibility for people within the country landscape,” he says today. “But I feel like I’m just doing what everyone from the dawn of time has done, which is writing about love. It’s not hard for me to do. I have a hard time not being honest; I REALLY hate lying. So it’s an easy responsibility, because I just get to go up there and be myself.”

Because his mystique is so carefully crafted and beguiling, certain social media sleuths have become obsessed with discovering who he “really is” and what he did before he became Orville Peck. He thinks they’re kind of missing the point: when DIY asks if we should really think of the mask as “a look,” he replies in a heartbeat: “100 percent!”

“I’m someone who grew up with the idea that any type of performance went hand in hand with an aesthetic and a production value and kind of being extra, you know?” he says. “I don’t really subscribe to the notion that something has to be boring or toned down for it to be sincere. I mean, this is the most sincere thing I’ve ever done in my life, and it’s obviously very extra-looking at times, but that’s part of who I am and part of who I like to be as an artist.” Orville finds it frustrating when anyone suggests his mask - or look - could detract from this sincerity. “I think it’s kind of shortsighted of people to think that the two things are mutually exclusive,” he says.

In this sense, Orville sees himself as a successor to country icons of the 1960s and 1970s – Dolly Parton, Johnny Cash, Merle Haggard – who operated at “this cool intersection of sincerity and theatricality.” Though the images they projected were larger than life, no one doubted that they meant what they sang. Legend has it that when Parton stays overnight in a hotel, she sleeps with a wig next to her so that she can even give us Dolly during a fire drill. Maybe we should think of Orville’s mask in a similar way: as an unnegotiable component of his public persona.

“I just didn’t give a fuck anymore. I felt like I had nothing to prove to anybody.”

In fairness, it's hard to argue with the raw emotional honesty that radiates from 'Bronco', his rollicking, rousing and often very moving second album. "I don't want you to be afraid, let me see you cry," he sings on 'C'mon Baby, Cry'. It sounds like a lost country classic from back in the day, but grapples with a very modern phenomenon: toxic masculinity.

Though Orville addresses 'C'mon Baby, Cry' to "a sad boy just like me," he says it's based on his own personal journey. "It's advice that someone gave me, because I used to be someone who found it hard to be vulnerable and say what I want and need," he says. "I found it hard to be kind to myself, to go easy on myself, to encourage myself, all of those things, for a very long time. For most of my life, actually. And I finally learned how to, so I guess that song is me sort of encouraging someone else to do the same."

It's no coincidence that 'Bronco' continues Orville's run of horse-themed record titles: he followed 'Pony' with 2020's 'Show Pony' EP, home to his Shania Twain duet and a fabulously dramatic cover of Bobbie Gentry's 1969 hit "Fancy'. On one level, the equestrian leitmotif plays into the singer's campy cowboy image. But on another, he says the titles tell us something about his headspace when making each record. "For me, 'Pony' was an album very much about loneliness," he explains. "And it was me putting myself out there for the first time, so I was feeling a little bit like a little scared, lonely pony." But, by the time 'Show Pony' came out less than 18 months later, his career had exploded. "Suddenly I had this kind of confidence, and [the music] was showy and glitzy and a bit more, you know, rhinestone-y, so that's why it was called 'Show Pony'," he says.

After the rhinestone-studded confidence of the 'Show Pony' era came an almighty crash that eventually gave birth to 'Bronco'. "I wrote this album coming out of a really terrible depression," Orville recalls. "I was ready to stop making music, my tour had just been cancelled because of Covid, my personal life was in shambles. And so I kind of did this big overhaul with my life." This involved writing songs solely for himself, "for the first time in ages," without trying to second-guess what Orville Peck should sound like. In time, a "beautifully cathartic" body of work started to take shape. "It just felt absolutely freeing," he says. "And when I looked at the end result, I thought, 'This is just so unrestrained and untamed and wild and free. And at that point it was obvious. I was like, "I think this one's called 'Bronco''."

“I really love being this source of [queer] visibility for people within the country landscape.”

Orville says his depression was caused by "a mixture" of personal and professional events, but as you'd expect, he's much more comfortable talking about the latter in specific terms. "It sounds a little silly, I suppose, but I had trouble getting used to this success that I'd found very quickly," he says. "There were so many new expectations on me from other people, and new expectations from myself, that I was kind of running on empty and burned out and uninspired. I didn't even have a home at the time because we were on tour; all my stuff was in storage." Then when Covid hit, he found he had no choice but to confront "the other part of my life that I had been ignoring and neglecting for a long time."

By confronting his demons head-on after being in such a "dark, unhappy place," Orville reached a point of "radical self-acceptance". "I just didn't give a fuck anymore," he says. "I felt like I had nothing to prove to anybody." Unsurprisingly given the album's soul-searching origins, strands of darkness are woven into 'Bronco''s rich tapestry. "I sat around last year wishing so many times that I would die," he sings on 'The Curse of the Blackened Eye', a song that alludes to a physically and emotionally abusive relationship.

'The Curse of the Blackened Eye' taps into country's capacity for tackling tough subject matter, but it also feels like an incredibly vulnerable moment for Orville. When he sings, "It ain't the letting go, it's more about the things that you take with / And I can feel it getting closer with every kiss," he seems to be suggesting that past relationship trauma still haunts him when he meets someone new. In characteristic fashion, though, he'll only be drawn so far into discussing what the song is about. "I kind of realised that I had this trauma following me around for a long time, and it still follows me around," he says. "It doesn't matter if I'm sitting in my hotel room alone or at the GRAMMYs, it's still always there just, you know, keeping an eye on me. And that's sort of what the concept for the song was." Where does this trauma come from? "I mean, I went through a heavy personal thing in my life, relationship-wise ..." is all he'll concede today.

'Bronco' also contains more wistful moments such as 'Blush', a song Orville calls his "love letter to London". When he sings "some of us, we gotta saddle up and ride," it's a stirring reminder of why he can lay claim to being the world's coolest cowboy. Because he has realised his artistic vision so beautifully, it's difficult now to imagine him, pre-fame, pinging around on the London Underground. But actually, he's happy to look back on this period of his life in relatively unambiguous terms.

“I'm kind of an East London boy," he says brightly. "I lived in London Fields and Stoke Newington for a long time. I used to hang out at The Glory, which is the gay pub in Homerton, and also at Dalston Superstore. But at the same time, I'd also hang out in Soho and bounce around all over the place." Soho? Surely he never frequented G-A-Y, a camptastic Soho bar where the only concession to country music might be Shania Twain commanding "let's go girls!" every so often. "I'm definitely more of an East London guy," he replies with a laugh, "but that's not to say I haven't been to G-A-Y and Heaven."

Orville looks back fondly on his London years because it was there that he began building the identity he presents today. "I was acting, doing a lot of classical theatre - Shakespeare, Chekhov - but I was also starting to write music again," he recalls. "I actually started working on 'Pony' at the tail end of my time living in London. You know, I was in my late twenties and it was like my second round of formative years in a way. I really found my autonomy and the kind of artist I wanted to be. I had this lightbulb moments of realising that I could do all these different things that I love, and put them into one thing and make it sincere."

“There’s a sense of relief and comfort with accepting who you are and being proud of the fact you are kind of an outsider.”

Though Orville Peck appeared to arrive in 2018 as a fully formed alt-country superstar - a glistening synthesis of traditional Nashville glitz and modern unapologetic queerness - what we see now is the butterfly that emerged from a sometimes uncomfortable cocoon. "I spent most of my life trying to be someone I wasn't, trying to be likeable, trying to change myself somehow to be successful," he admits. "But at some point, that just gets old. There's a sense of relief and comfort with accepting who you are and being proud of the fact you are different and kind of an outsider."

Rather touchingly, he says being hired by Beyoncé for last year's Ivy Park Rodeo campaign erased the last traces of his imposter syndrome. "It just gave me this, like, really obvious and loud sort of validation," he says. "I was like, "OK, Beyoncé knows who you are and she likes what you do. And she wants to have you as part of this thing she does'. I mean, what could be more affirming than that?"

Being an outsider is as fundamental to Orville's identity as being a cowboy: for him, the two go hand-in-hand. As a lonely kid who "always felt out of place," he was drawn to the strong, solitary and yes, homoerotic image of the cowboy as a kind of proud lone ranger. "Even though I didn't know it at the time," he says, "I think I connected with it because it was the only character I saw who was an outsider and a loner, but had that celebrated as their power rather than their weakness. The cowboy was always coming into town to save the day."

Ever since then, Orville has felt country to the core, but also like a punk. "You know, I played in punk bands for a long time, I was a drummer," he says. "And I feel like there are a lot of parallels between punk and country music because they're both about challenging the status quo. Female country feels very punk to me because it's about challenging the patriarchy."

Orville characterises Lil Nas X - who climbed the charts in 2019 with 'Old Town Road', an innovative country-trap hybrid, then came out as gay when it was number one - as the genre's latest major disruptor. "The funny thing about country is that it goes through this cycle every generation or so," he says. "When Willie Nelson first came out [in the 1960s], everyone in Nashville was flipping out - like, who is this hippie singing about smoking weed? Then when Shania Twain got to Nashville [in the 1990s], people were like: "This isn't country, it's pop music. She's showing her belly button and being provocative.'"

For Orville, this cycle is what makes country "subversive," or at least gives it the potential to be. He has no real affection for cookie-cutter country songs about "trucks and beer" because "that's not really coming from a place of challenging people's thoughts, or telling a story that's gonna intrigue them". "But," he continues, "when 'Old Town Road' came out in 2019, that made total sense to me, because it's challenging the idea of what country music can be and actually evolving the genre."

With time coming to an end, DIY asks about Orville's favourite Dolly Parton song, "Tennessee Homesick Blues'. Written for her 1984 film Rhinestone, it's a sleek and shiny country bop with layers of longing, regret and steely determination lurking just beneath the surface. When Parton delivers the payoff line - "it's hard to be a diamond in a rhinestone world" - it could almost be a mantra for her entire career.

“That's my favourite line in the song, and kind of my favourite Dolly line in general," Orville says. "Without wishing to sound conceited, I grew up as a very singular kind of kid. I was always different and super creative, and for the longest time I was sort of bullied into thinking that was a weakness. But as I've gotten older - and I say this because it took me a long time to get there, like 30 years - I recognise that me being a diamond in a rhinestone world is ABSOLUTELY my strength."

Most excitingly of all, this diamond hasn't even been buffed to his full sheen yet. "I feel like I'm in the healthiest place of my life at the moment," he says. "I'm honestly just raring to go."

'Bronco' is out 8th April via Columbia.

As featured in the April 2022 issue of DIY, out now.

Read More

Orville Peck - Bronco

4 Stars

It flits between theatricality and poignancy.

8th April 2022, 12:00am

Rina Sawayama, Orville Peck and Joesef unveil three new covers for Spotify Singles x Pride

The new campaign sees the three emerging LGBTQ+ artists paying tribute to their musical faves.

29th June 2020, 12:00am

Orville Peck announces new ‘Show Pony’ EP

And he's sharing new track 'No Glory In The West' to celebrate!

29th May 2020, 12:00am

Tracks: The Streets, Phoebe Bridgers, Alison Mosshart and more

The biggest and best tracks of the past few weeks, rounded up and reviewed.

17th April 2020, 12:00am

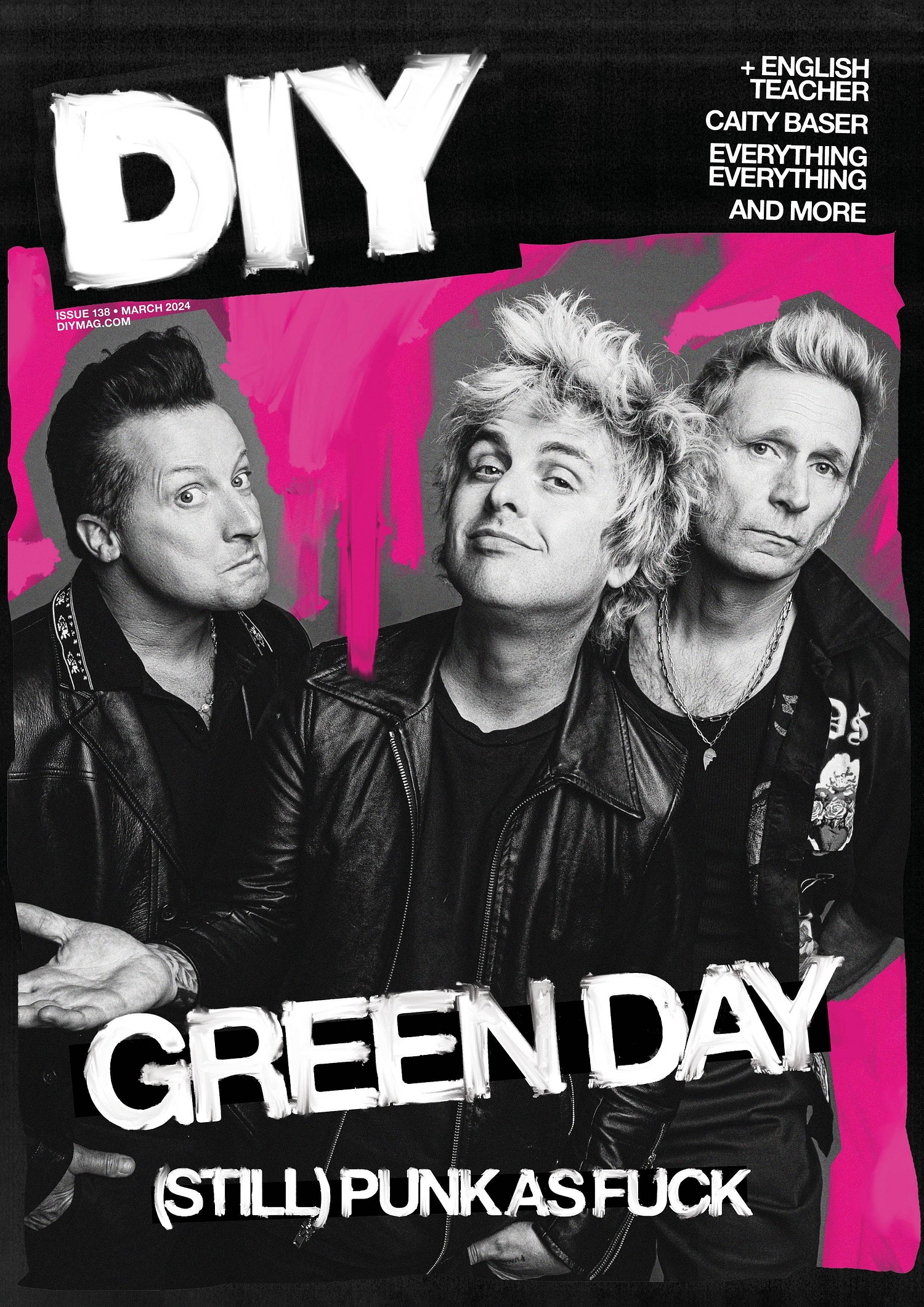

Popular right now

Featuring Green Day, English Teacher, Everything Everything, Caity Baser and more!