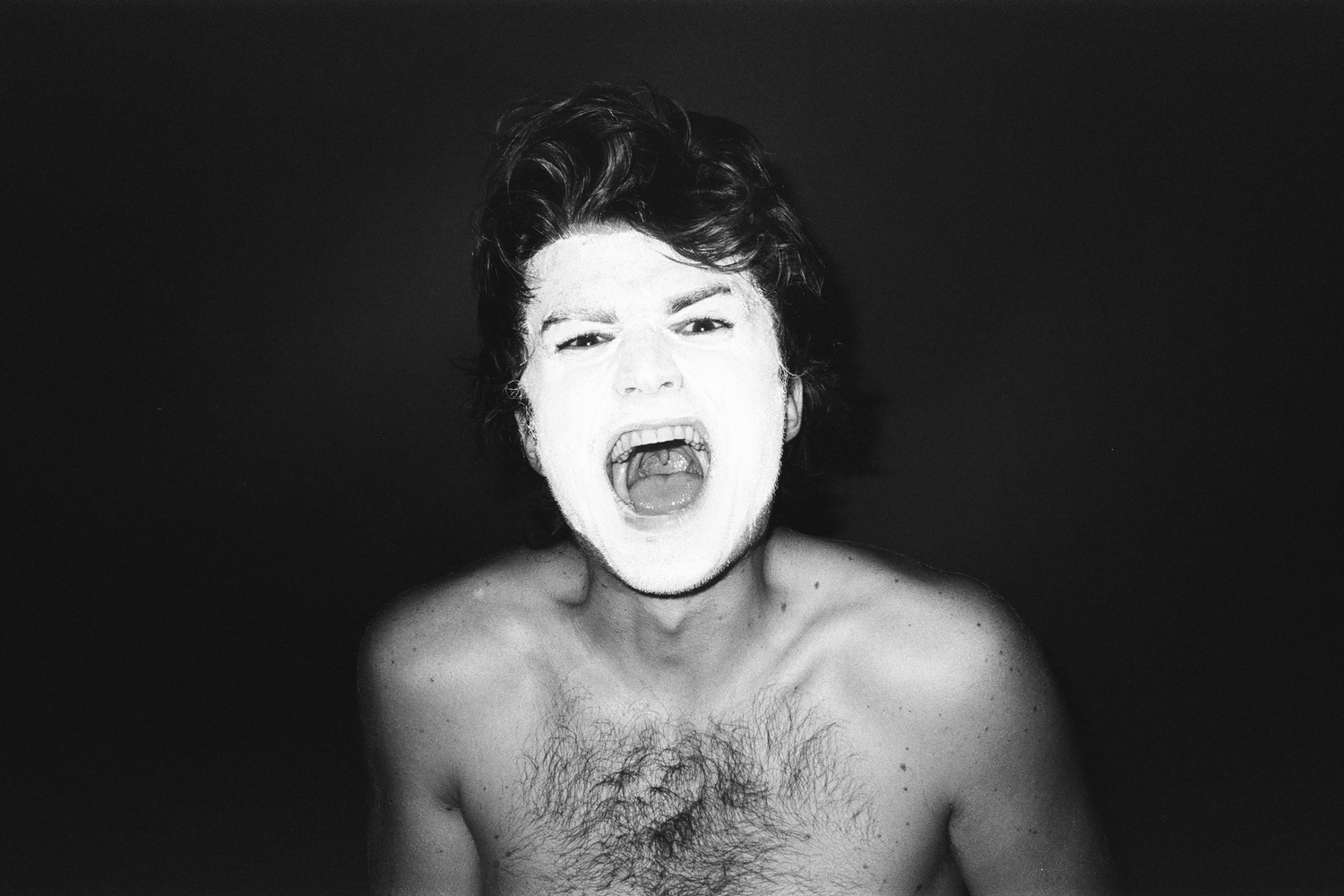

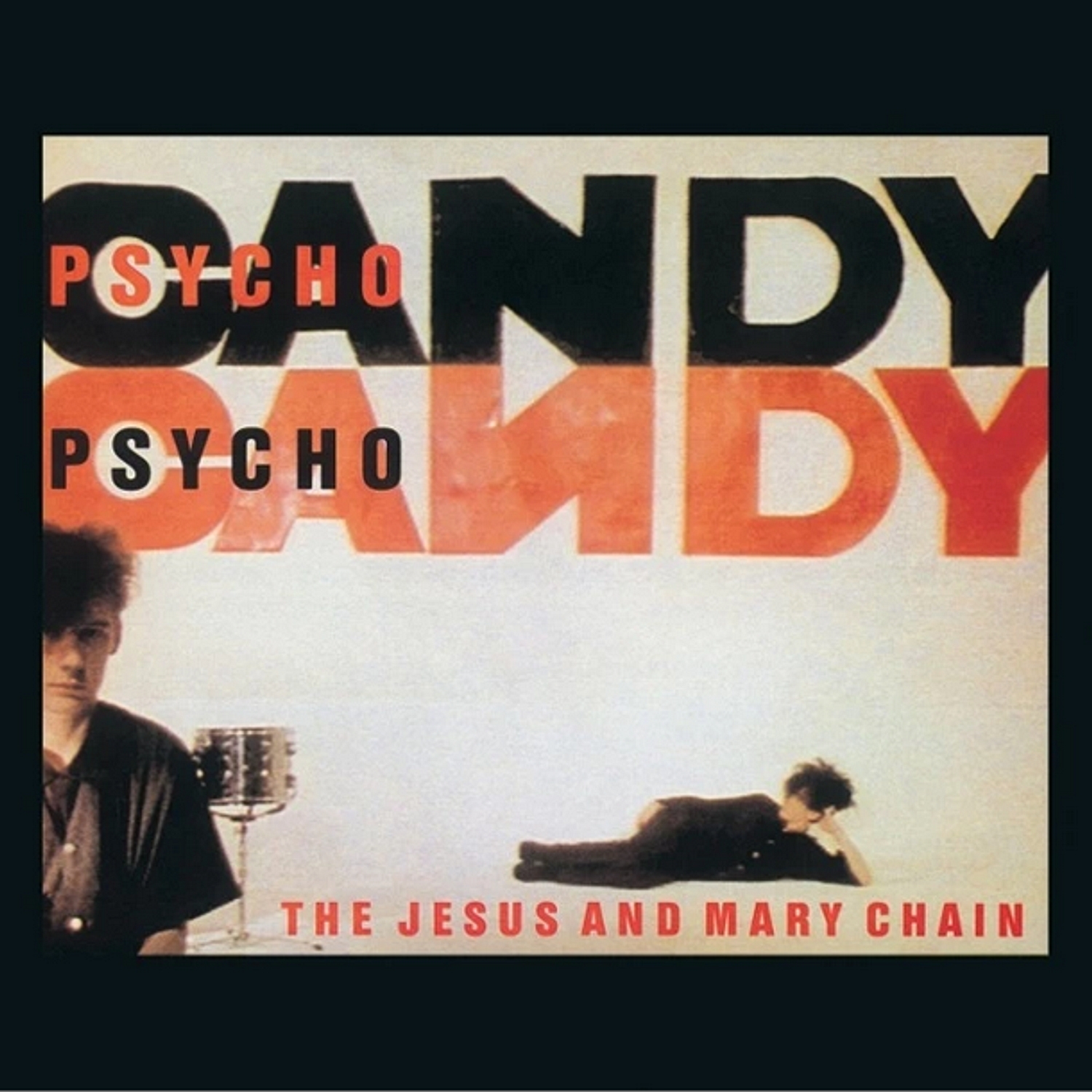

Interview “Indie had become a celebration of failure”: The Jesus and Mary Chain on thirty years of ‘Psychocandy’

This is more than just a revivalism, says Jim Reid, as he looks back on a treasured LP and discusses future plans with Joe Goggins.

Sometimes, the eighties seems like such a self-contained period that you could probably count on one hand the number of things that didn’t feel laughably dated ten years later, let alone thirty. If that was the case, you’d have to include The Jesus and Mary Chain’s ‘Psychocandy’ amongst them; even now, three decades down the line, the way in which they took melodic pop music and drowned it in aggression, distortion and punishing volume feels a little space age. They understood the potential of the guitar as a piece of genuine sonic weaponry before My Bloody Valentine. They understood the ingenuity of dressing up pop songs as rough and ready rock before Nirvana got there. They realised, in an era dominated by an avalanche of chart cheese, that mainstream success and real innovation didn’t need to be mutually exclusive.

When Jim Reid formed the band with his brother, William, they had plans for world domination; circumstances ultimately conspired to prevent that, though, not least the culture of chaos that ended up following the band everywhere they went in the wake of ‘Psychocandy’’s 1985 release. A mixture of anxiety-driven drinking and decidedly unpolished musicianship meant that early Mary Chain live shows were ramshackle affairs, with messy sets seldom lasting longer than twenty minutes. The unrest that inspired in the crowds led to riots, and the more the band earned themselves a reputation for violence and havoc, the more people were attracted to their gigs purely to partake in the disorder.

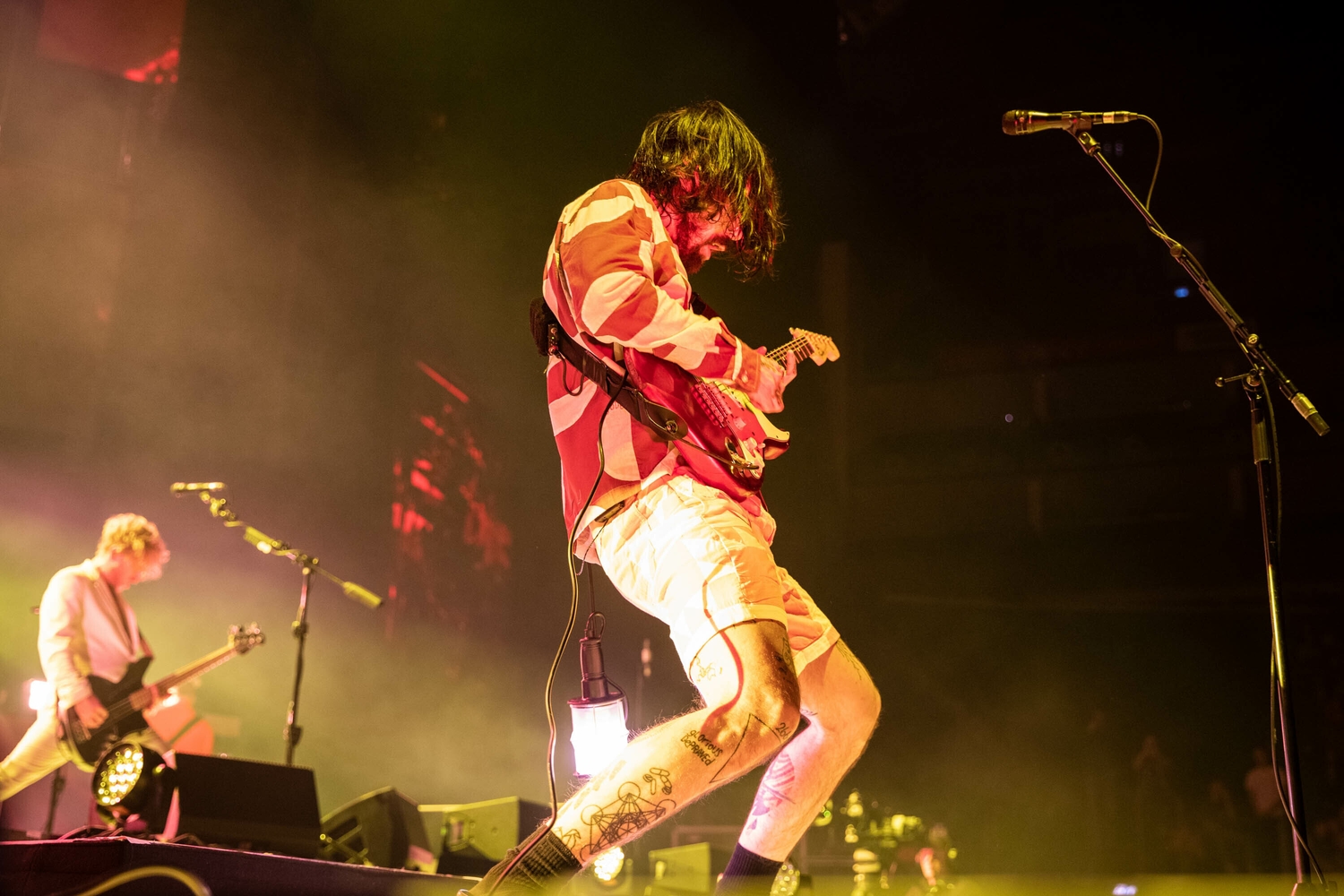

And, yet, that period wasn’t totally unrepresentative of ‘Psychocandy’. The record does carry with it a certain menace; the harsh soundscapes do hint at a sense of imminent danger, and accordingly, the atmosphere of that period has become inextricably linked to the album itself. Last year, though, to mark its thirtieth anniversary, the recently-reconciled Reids resolved to take it back on the road, and this time do it sonic justice - airing in its entirety, with a slew of the songs never having been played previously. The success of the tour, which has now run well into this year, is reflected in the release of ‘Psychocandy Live’, a document of last year’s appearances at the Barrowlands in Glasgow; as Jim Reid acknowledged when we spoke to him last month, both band and album have seldom sounded quite this loud, and quite this uncompromising.

How have the ‘Psychocandy’ shows been going so far?

They’ve gone quite well. We really had no idea of how it was going to go over; at one point in time, we couldn’t really imagine doing this kind of thing at all. There’s been no problems whatsoever though. The reaction’s been pretty good, and we’ve been playing it pretty well.

Were you reluctant to commit to these shows in the first place? A lot of artists seem to think tours like these are regressive, and just nostalgia trips.

We were, yeah. People have been trying to get us to do this for years, but we never really saw the point before. By the time it was coming to the thirtieth anniversary, we talked about it again, and kind of came to the realisation that either we do it now, or we never ever do it. It would have been too late after this; I mean, thirty-fifth or fortieth anniversary - Christ! I might be dead by then. We sort of weighed up the reasons for and against, and a big thing we thought about in favour of doing it was that a lot of the songs on the album had actually never been performed live ever, anywhere, and that seemed like a shame, and a bit of a waste. In the end, we thought, “fuck it.” Why the hell not?

I know people aren’t always in favour of these kinds of gigs, and they can make of it what they will. I don’t care. If you don’t think it’s a good idea, don’t come to the shows, don’t do it yourself if you’re in a band. It’s totally up to you.

Was there a sense that you wanted to do ‘Psychocandy’ justice on stage all these years on? The way the shows around it went down in the eighties meant it was never really given a proper live outing.

Definitely. I mean, that was kind of one of the reasons we actually resisted in the beginning. Whenever somebody suggested we do ‘Psychocandy’ shows, we thought that the chaos and the violence was perhaps too much what people associated with the album, and that maybe they’d be expecting something that we didn’t want to provide. It’s daft, really; it’s just an album, you know? It’s just a rock record, so why don’t we get out there and make it a celebration of what it actually was, rather than let the legacy of it be all that nuttiness that followed the band around for a time? We wanted to celebrate the fact that it still means something, all these years later.

Photos: Carolina Faruolo / DIY.

Do you think you could even have made ‘Psychocandy’ if you were starting a band now, rather than thirty years ago? It’s kind of hard to envisage anybody being able to go down to London without much money or, by your own admission, much knowledge of how to play or record and be able to turn out something so timeless.

I don’t think we could, but it’s nothing to do with geography. London’s always been expensive, and when we were down there, it was definitely difficult to make ends meet. That’s how it’s always been. It’s the state of the music business that’s against you nowadays. It’s basically a sinking ship.

How so?

Nobody’s buying records anymore. The album seems to be a dying format - people aren’t interested. They want little bitesize pieces of music now; they aren’t looking for a physical piece of work that you spent months, or maybe years, putting together. It feels like everything’s shrinking - like it’s dissolving, almost. You speak to a sixteen-year-old kid now and say, “oh, we’re recording an album,” and chances are they won’t know what the fuck you’re talking about. “You mean you’re recording a handful of songs, one or two of which I might be interested in downloading?” And maybe for free, at that. That’s how it is, now. That’s what new bands are up against.

There must be an upside to the internet for the Mary Chain too, though - I was at the ‘Psychocandy’ show in Manchester last November, and there were a lot of people there - judging from how young they were - who must have discovered the record that way.

Oh yeah, for sure. There’s been a lot of young people at every show, and for us, it’s obviously better than looking out on a sea of middle-aged guys, because you know it can’t be about nostalgia. There’s kids who won’t even have been born when the album came out, and that’s been the case everywhere - from America to Dusseldorf. It’s very encouraging.

‘Psychocandy’ was actually fuelled by a disaffection with the industry at the time you were writing it, right?

Yeah. I think it was the fact that, when we were growing up, it was all Bowie, Mott the Hoople and T. Rex. You turned Top of the Pops on, and that was what you got - proper pop bands. By the eighties, there was just nothing like that left in the mainstream; if you wanted to watch TV or listen to Radio 1 during the day, it was going to be Duran Duran or Spandau Ballet that you’d hear. Bands that made us feel sick, basically. The kind of music that excited us when we were kids was being pushed underground; stuff like Sonic Youth, those really great bands that were being ghettoised by the time we came along.

What we wanted to do - and this confused a lot of people at the time - was take what by then was being called ‘indie’ music and move it back to where it had been before. Indie had become like a celebration of failure, and we wanted to bring it back to Top of the Pops, and we wanted to play big venues. We felt pretty good about it, too - we weren’t interested in being in this indie ghetto. I wanted to be Marc Bolan. I wanted to be a pop star, basically, and that’s what ‘Psychocandy’ was about.

Do you think those aims ended up being derailed by what happened when you started touring ‘Psychocandy’?

Not necessarily. I mentioned T. Rex and Bowie, but we’d also just come up through punk as well, and we all kind of thought that not only did the bands who were dominating the charts in the eighties sound awful, but they had no attitude, either. They had no teeth, no sense of danger, and I think we felt we could revive that, and bring back a DIY punk ethic that retained the rough edges without that necessarily meaning that we couldn’t be in the charts. I think we were just appalled by people’s values in the industry. I mean, eighties values were pretty horrendous right across the board, if you think about it. It was all about greed, Armani suits and a general air of “I’ve got more than you.” It was awful.

Politically speaking, there’s obviously some parallels between the period in which ‘Psychocandy’ was released and now, when you’re out playing these shows.

That’s true, and whilst I think some of that disaffection informed the songs, we were never an overtly political group. I’ve never liked it when bands use that particular platform in that way. People should make up their own minds about who they want to vote for, and at the time, I found that whole fucking Red Wedge thing hugely embarrassing, even if I might have agreed with what they were saying. If you want to be a politician, go and be a politician, but don’t be a rock star who thinks you can change people’s points of view. That was never our thing.

Funny you should mention that, because Live Aid was thirty years ago today.

Well, that’s exactly what I’m talking about. I certainly remember, at the time, finding that whole exercise rather cynical. It was less about feeding starving people and more about selling records, and that’s the truth. That’s exactly what drove it. I remember, back then, knowing somebody who worked in Virgin Megastores on Oxford Street, and she said that in the aftermath of it, the back catalogues of the artists involved were selling something like five times what they’d normally be expected to. They didn’t give any of that money away to charity, you know what I mean? They might have given tuppence ha’penny away that they made on the day for playing, but they were all getting fucking rich as well, you know?

"We haven’t recorded anything, but we’ve got a bunch of demos and we’re looking at starting to record it some time in the near future."

— Jim Reid

This new live record was recorded in Glasgow, which is the nearest thing to a hometown gig as the Mary Chain usually get. Do you think the small town nature of East Kilbride informed ‘Psychocandy’ back when you were making it?

It had to have done, really. Growing up in a place like East Kilbride very much gives you an outsider’s point of view; you kind of feel as if you’re looking at the rest of the world through a telescope. It gives you this odd, skewed outlook on the world. It must have had some importance to the way things turned out for us; I do wonder whether, if we’d been born and raised in central London, whether we’d have ended up with the same mindset that led us into making music. I don’t know if it would have happened for us. The distance - that sense of alienation, of being a long way from where everything was happening - obviously had an impact on how we thought about things.

At the shows, the ‘encore’ of post-‘Psychocandy’ material has actually been preceding the record itself. What was the thinking behind that?

It was William’s idea. I think we kind of assumed that people would want to hear more material on the night, because the album’s only about forty minutes long, but William was really hung up on the idea of not wanting to play any more music after ‘Psychocandy’, that ‘It’s So Hard’ should be the last track on the setlist. So, very presumptuously, we played the newer stuff first - including ‘Some Candy Talking’, which was never meant to be on ‘Psychocandy’ - so that the last music played would be the album itself.

How meticulously did you follow the sound of the recorded versions of these songs when you were rehearsing them?

As closely as we could, really. I mean, you have to remember that we pretty much had this album mapped out before there was even a band. William and I always had this idea of what the perfect record would sound like. We’d sit up all night and wonder why people didn’t make music like such and such, and we’d draw up a blueprint for the perfect album, or the perfect band. With everything else, too; you know, why hasn’t anybody made this film yet? We’d be drawing sketches of the perfect movie or book or whatever, but because we couldn’t make films - and we weren’t much cop as novelists, either - we started a band, and went on to make what, for us, was the perfect album. And that was ‘Psychocandy’.

Did that put extra pressure on you to make sure it sounded exactly right?

That was one of the scary things about it. The idea of going out there, doing it and it then not sounding like Psychocandy - that’s a bit of a disaster. I’ve never seen one of these full album shows from the audience before, but you do see other bands reworking their old material, and it never comes off. We really, desperately didn’t want it to be like that. It needed to be the most accurate representation of the album as we could manage. As far as it still being the perfect record to us, it’s probably not, but it was in 1985. Now, it just sits as a snapshot of us at the time, I think.

Is there ever going to be another Mary Chain record?

Yeah, we actually are going to do another album, for what it’s worth. We’ve talked about it for quite a long time now, and we’ve argued about for quite a long time now, but we finally seem to be talking the same language. We haven’t recorded anything, but we’ve got a bunch of demos and we’re looking at starting to record it some time in the near future. So there’s going to be another one, and hopefully soon.

The Jesus and Mary Chain's ‘Psychocandy Live’ is out now via Edsel.

Read More

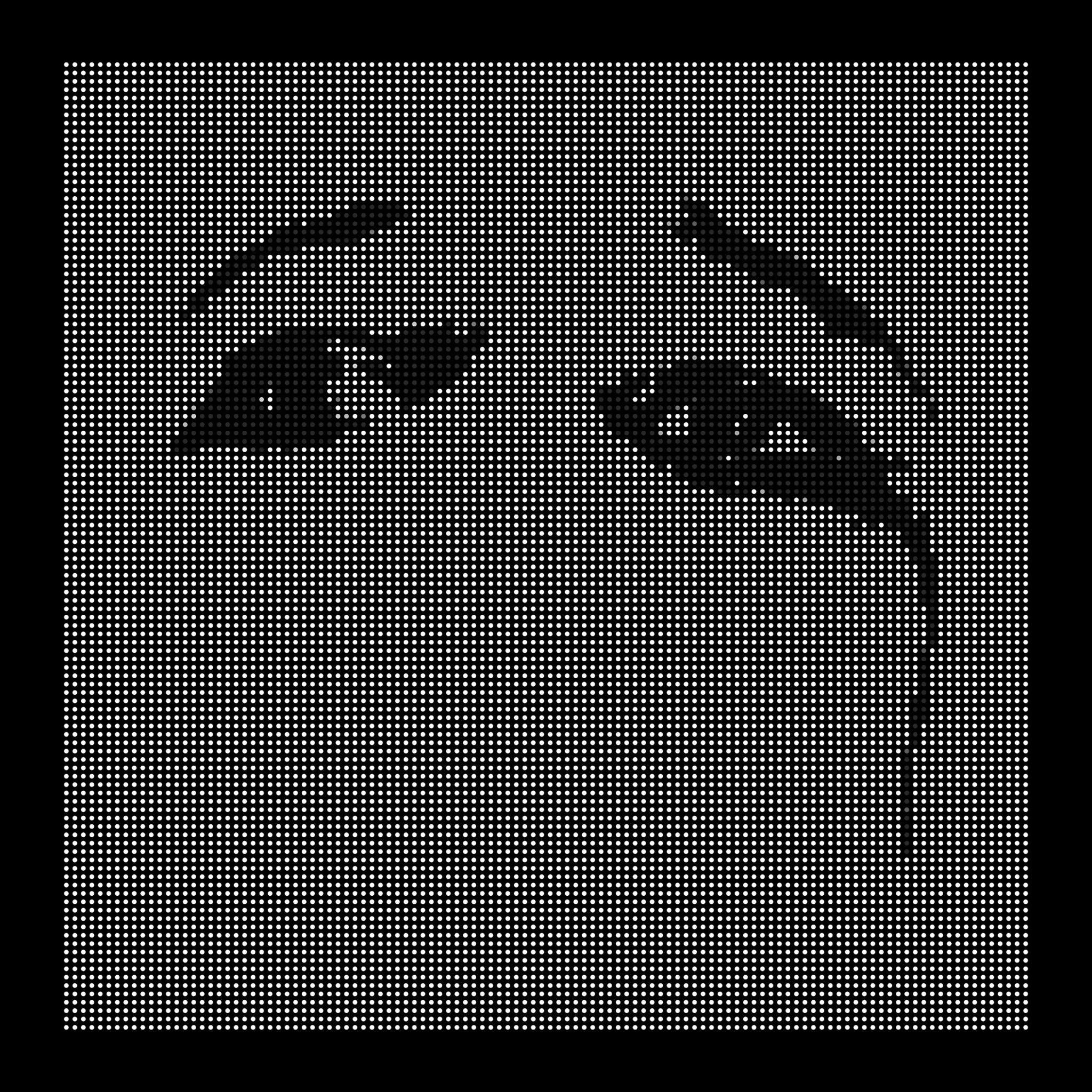

The Jesus and Mary Chain - Glasgow Eyes

3-5 Stars

The band appear to have tapped into a rich new vein of songwriting form.

6th March 2024, 8:00am

Green Man unveils Big Thief, Sampha, Sleaford Mods and more for 2024 lineup

Tickets for the Welsh festival sold out before any artists had been confirmed.

1st March 2024, 10:26am

The Jesus and Mary Chain & Aurora added to Ypsigrock 2018

They join The Horrors and Shame on the line-up for the Sicilian festival this summer.

28th March 2018, 12:00am

The Jesus and Mary Chain team up with Sky Ferreira on ‘The Two Of Us’

The new version of the track follows their collaboration on Colbert in May.

25th August 2017, 12:00am

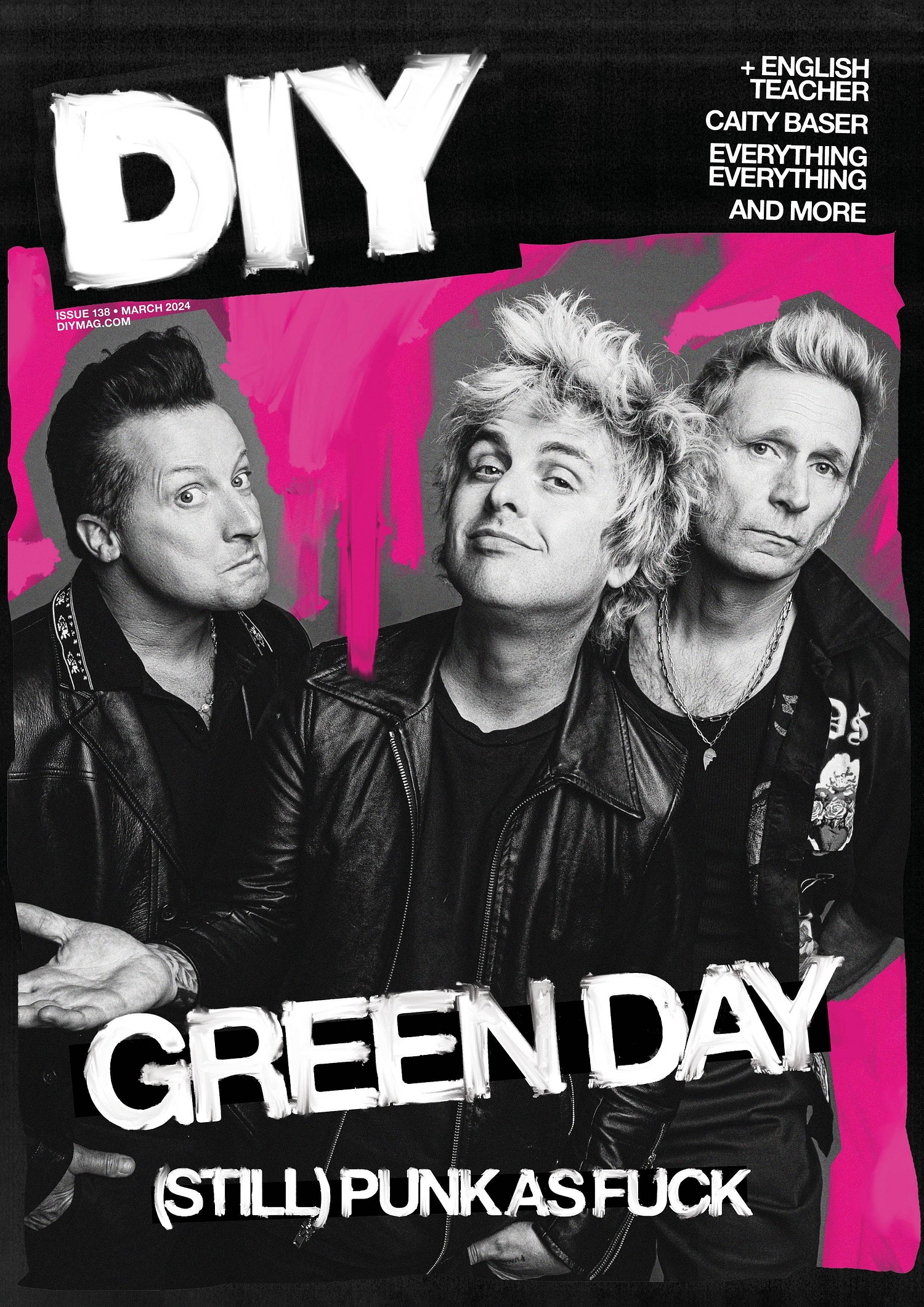

Popular right now

Featuring Green Day, English Teacher, Everything Everything, Caity Baser and more!